Beyond Gold and Grain: What Did Ancient Egyptians Trade Globally?

What did ancient Egyptians trade—and why did it matter so much to the shape of their civilization?

Short question. Long shadow. Because when you trace the trade routes of Ancient Egypt, you’re not just following ships and caravans; you’re following power, survival, and ambition itself. A civilization built along a narrow ribbon of the Nile could not afford isolation. What it lacked in raw materials, it learned to acquire through exchange—carefully, strategically, and often across dangerous distances. Gold moved north, cedar drifted south, incense crossed deserts, and ideas traveled with them all.

This is not a story about simple barter. It’s a story about how trade turned Egypt from a fertile valley into a Mediterranean and African powerhouse—and how what ancient Egyptians traded reveals what they valued most.

Table of Contents:

Togglewhat did ancient egyptians trade?

- Imagine a civilization rich in grain yet poor in wood, stone, and metals. That imbalance is the key to understanding what did ancient Egyptians trade—and why trade was never optional for them.

- Ancient Egypt exported what the Nile gave generously. Grain topped the list, especially wheat and barley, shipped during surplus years to neighboring regions.

- Alongside food came linen, woven from locally grown flax and prized for its quality, and papyrus, Egypt’s quiet monopoly, used for writing, administration, and diplomacy. Add to that gold from Nubia, jewelry, faience, perfumes, and crafted goods, and you begin to see Egypt’s economic leverage.

- What came in tells the other half of the story. Egypt imported what its land could not provide. Cedarwood from Lebanon was essential for ships and coffins. Copper and turquoise arrived from Sinai, while silver, rare in Egypt, came from Anatolia and the Aegean. From Punt—still debated but likely along the Red Sea coast—came incense, myrrh, ebony, ivory, and exotic animals, goods tied as much to religion as to prestige.

- Trade moved along two lifelines: the Nile River, acting as a natural highway, and overland desert routes guarded by forts and wells. Much of this exchange was state-controlled. Pharaohs didn’t just rule; they negotiated, commissioned expeditions, and displayed foreign goods as proof that order extended beyond Egypt’s borders.

- So when we ask what did ancient Egyptians trade, the honest answer is this: they traded survival for strength, surplus for influence, and everyday goods for symbols of power.

From Local to International Trade

- Every economy starts small. Egypt was no exception. Before ships crossed seas and caravans vanished into deserts, trade in Ancient Egypt began locally, village to village, province to province, following the steady rhythm of the Nile.

- At the local level, exchange was practical and intimate. Farmers traded grain for tools, fishermen exchanged fish for linen, and craftsmen swapped labor for food. Money didn’t exist in the early periods. Value was measured instead in deben, a weight-based unit used to compare goods. Simple system. Surprisingly efficient. And it answered a basic question early Egyptians faced: how do you move surplus from where it exists to where it’s needed?

- Then the scale changed.

- As the Egyptian state centralized, trade moved beyond survival into strategy. The Nile turned into an economic spine, allowing goods to travel hundreds of kilometers with minimal effort. Royal granaries redistributed food. Workshops supplied temples. Suddenly, trade wasn’t just economic—it was administrative.

- International trade pushed things further. Egypt looked outward because it had to. Timber, metals, luxury items—none came easily from the Nile Valley. So expeditions were organized, routes secured, and foreign relations carefully managed. Trade with Nubia brought gold and ivory. Levantine ports supplied cedarwood. Sinai offered copper and turquoise. Expeditions to Punt delivered incense so vital it fueled religious rituals themselves.

- Here’s the quiet shift most people miss: international trade was rarely private. It was state-driven, led by officials, scribes, and soldiers. When Egypt traded beyond its borders, it wasn’t just exchanging goods—it was projecting order, wealth, and control.

- So the journey from local to international trade mirrors Egypt’s rise itself. Small exchanges built stability. Long-distance trade built power. And together, they explain how a river-based society became a civilization others depended on.

Read:

Why Trade Was Essential for the Egyptian Civilization?

- No civilization survives on abundance alone. Egypt’s fields overflowed with grain, yes—but beyond the Nile’s green banks stretched scarcity. That tension explains why trade wasn’t a luxury for Ancient Egypt. It was a necessity.

- Start with the obvious problem. Egypt lacked timber, silver, copper in large quantities, and quality stone in many regions. Ships, temples, tools, weapons—none of these could exist without materials from elsewhere. Trade solved a structural weakness. Without it, Egypt would have remained fertile yet fragile.

- But necessity quickly turned into advantage.

- Trade stabilized society. When floods were generous, surplus grain flowed into state granaries and outward to trading partners. In lean years, those same connections softened crisis. Food security wasn’t just agricultural—it was diplomatic. This is a core answer to why trade was essential for the Egyptian civilization.

- There’s a political layer too. Long-distance trade justified state organization: scribes to record goods, officials to manage expeditions, soldiers to protect routes. Trade strengthened central authority, and central authority made trade safer. Each fed the other.

- Religion adds another dimension. Temples required incense, resins, gold, and exotic offerings—many unavailable locally. Without trade, daily rituals honoring the gods would have stalled. And in Egyptian thinking, disrupted rituals meant disrupted cosmic order. Trade, in this sense, upheld ma’at itself.

- Then comes power and perception. Foreign goods displayed in temples and tombs weren’t decoration. They were messages. Egypt could reach you. Egypt could acquire what others could not. Trade turned geography into influence.

- Strip trade away, and Egypt loses more than materials. It loses resilience, authority, religious continuity, and reach. That’s why trade wasn’t peripheral to Egyptian civilization—it was one of its load-bearing pillars.

Main Goods Traded by the Ancient Egyptians

- If you want the clearest answer to what did ancient Egyptians trade, don’t start with lists. Start with logic. Egypt traded what it had in excess—and chased what its land refused to give.

- Grain sat at the center of everything. Wheat and barley, harvested thanks to predictable Nile floods, were Egypt’s most reliable export. Grain fed neighboring regions during shortages and doubled as political leverage. When Egypt traded grain, it wasn’t just selling food; it was selling stability.

- Next came linen. Made from locally grown flax, Egyptian linen was valued for its fineness and durability. It clothed workers, wrapped mummies, and moved across borders as a symbol of quality craftsmanship. Alongside linen traveled papyrus, a near-monopoly product used for writing, contracts, and record-keeping across the ancient world.

- Then there was gold—not myth, but logistics. Mines in Nubia supplied Egypt with enormous quantities, enough to fund temples, diplomacy, and long-distance trade. Gold jewelry, amulets, and raw bullion flowed outward, reinforcing Egypt’s image as a land of wealth.

- Imports reveal Egypt’s dependencies. Cedarwood from Lebanon was essential for ships, doors, and coffins. Copper and turquoise arrived from Sinai, vital for tools and ornamentation. Silver, rare within Egypt, came from Anatolia and the Aegean. From Punt came incense, myrrh, ebony, ivory, and exotic animals—goods tied directly to religious ritual and royal prestige.

- Crafted items mattered too. Egypt traded faience, glassware, perfumes, and jewelry, proving that skill could be as valuable as raw material. These weren’t mass exports; they were statements of refinement.

- So when you line it all up, the pattern is clear. Ancient Egyptians traded food, craftsmanship, and gold outward—and drew in the materials that sustained their economy, religion, and power. The goods tell the story. Balance, not abundance, kept the civilization standing.

Also read:

Imports: What Egypt Brought from Other Lands

- Here’s the uncomfortable truth: for all its power, Ancient Egypt was materially incomplete. The Nile gave food and order—but it did not give everything. Imports filled the gaps, and those gaps mattered more than they seem.

- Start with wood. Egypt had palms and acacias, nothing suitable for large ships or monumental architecture. So cedarwood from Lebanon became indispensable. It arrived as beams for boats, doors for temples, and coffins for elites. If Egypt wanted to sail, build, or bury with dignity, it needed foreign forests.

- Then came metals. Egypt had gold in abundance, but silver was rare enough to be more valuable than gold at times. It flowed in from Anatolia and the Aegean world, used for high-status objects and temple wealth. Copper, critical for tools and weapons, came mainly from Sinai, along with turquoise, prized both for jewelry and symbolism.

- Religion pulled Egypt even farther outward. Temples demanded incense and myrrh, substances not grown along the Nile. These arrived from the fabled land of Punt, likely along the Red Sea coast. Along with resins came ebony, ivory, animal skins, and exotic animals—materials that turned ritual into spectacle and reinforced royal authority.

- Stone, surprisingly, was also imported at times. While Egypt had limestone and sandstone, harder stones and special varieties were sourced through trade or controlled expeditions. Even luxury items like lapis lazuli, sourced ultimately from regions as distant as Central Asia, found their way into Egyptian jewelry through long trade chains.

- So when asking what did ancient Egyptians trade, imports reveal the deeper answer. Egypt didn’t trade because it wanted variety. It traded because key pillars of its economy, religion, and technology depended on materials from beyond its borders. Foreign goods weren’t optional extras. They were structural.

Related:

Exports: What Egypt Sold to Other Civilizations

- Think of Ancient Egypt as a land that always had something others needed. Its exports weren’t accidental; they were the natural outcome of geography, skill, and surplus coming together.

- At the top of the list was grain. Thanks to the Nile’s predictable floods, Egypt often produced more wheat and barley than it consumed. This surplus moved outward to the Levant, Nubia, and the eastern Mediterranean, especially during regional shortages. Grain exports weren’t just economic—they bought loyalty, peace, and influence.

- Next came linen. Egyptian linen had a reputation. Made from finely processed flax, it was lighter, cleaner, and more durable than alternatives elsewhere. Linen garments, ritual cloths, and burial wrappings traveled widely, carrying Egypt’s craftsmanship with them.

- Then there was papyrus—quietly powerful. Egypt controlled the plant and perfected its processing, turning papyrus into the ancient world’s preferred writing surface. Contracts, letters, and administrative records across the Mediterranean often depended on Egyptian exports.

- Gold deserves its own pause. Sourced mainly from Nubia, Egyptian gold flowed outward as raw metal, jewelry, and diplomatic gifts. It financed alliances, rewarded foreign rulers, and reinforced Egypt’s image as a land of unmatched wealth.

- Craft goods completed the picture. Egypt exported jewelry, faience, glass vessels, cosmetics, perfumes, and carved stone objects. These weren’t bulk shipments. They were high-status items, traded for prestige as much as for material return.

- So when asking what did ancient Egyptians trade, exports reveal Egypt’s strengths. Food, refined materials, and skilled workmanship formed the backbone of its outward trade. Egypt didn’t just sell goods—it exported reliability, quality, and power.

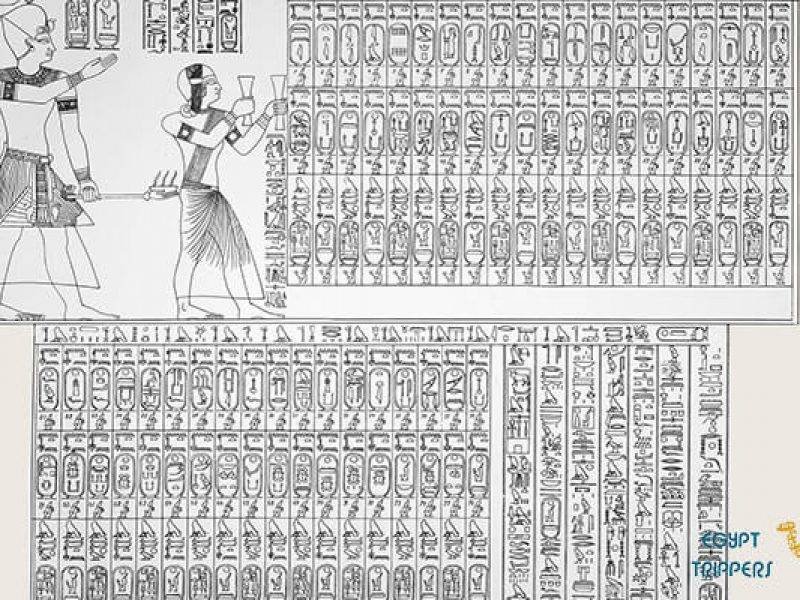

Trading Partners of Ancient Egypt

- Trade only matters if someone stands on the other end of the exchange. For Ancient Egypt, those partners formed a wide, carefully maintained network—stretching south into Africa, east into Asia, and north across the Mediterranean.

- Nubia was Egypt’s most consistent partner and rival. Located to the south, Nubia supplied gold, ivory, ebony, animal skins, and enslaved labor. In return, Egypt sent grain, finished goods, and political pressure. Trade here often blurred into control; when access to Nubian gold mattered too much, Egypt didn’t negotiate—it occupied.

- To the northeast lay the Levant—modern-day Lebanon, Syria, and parts of Palestine. This region mattered for one reason above all: cedarwood. Egyptian ships, temples, and elite coffins depended on Levantine timber. Along with wood came wine, olive oil, and luxury goods, while Egypt paid largely in grain, gold, and manufactured items.

- The Sinai Peninsula functioned less like a partner and more like a resource zone. Expeditions were sent regularly to extract copper and turquoise, materials vital for tools, weapons, and jewelry. These missions were organized, guarded, and recorded—trade mixed with state logistics.

- Across the Red Sea stood the enigmatic land of Punt. Whether located in the Horn of Africa or southern Arabia, Punt supplied Egypt with incense, myrrh, ebony, ivory, gold, and exotic animals. Trade with Punt was celebrated in reliefs and inscriptions, not because it was frequent, but because it was prestigious. Punt represented access to the rare and the sacred.

- To the north and northwest, Egypt interacted with the Aegean world, including Minoan Crete and later Mycenaean Greece. These connections brought silver, fine pottery, and luxury items, while Egyptian gold, papyrus, and crafted goods flowed outward.

- So when we map the trading partners of Ancient Egypt, a pattern emerges. Each partner filled a specific need—wood, metal, incense, prestige—and Egypt tailored its relationships accordingly. Trade wasn’t random outreach. It was targeted, deliberate, and deeply tied to survival and status.

Transportation and Trade Routes Along the Nile

If trade was Egypt’s lifeblood, the Nile was its bloodstream. Without it, the entire system collapses.

Look at the map and the logic becomes obvious. Egypt stretches long, not wide.

- The Nile runs straight through it. Flowing north, steady and predictable, the river turned distance into convenience. Heavy goods—grain, stone, timber, statues—moved by boat far more easily than by land. Sailing south was just as clever: ships raised sails and let the prevailing winds do the work. Few ancient civilizations enjoyed that kind of natural efficiency.

- River transport dominated internal trade. Flat-bottomed boats, built for shallow waters, carried agricultural surplus from rural estates to royal granaries, temples, and cities. Taxes were often paid in goods, not coins, and the Nile made redistribution possible. Administration followed the river because movement followed the river.

- But the Nile was more than an internal highway. It connected Egypt to the outside world.

- At the delta, Nile routes merged with Mediterranean sea trade, opening access to the Levant, Cyprus, and the Aegean. Ports became exchange points where Egyptian grain, papyrus, and gold met foreign timber, metals, and luxury goods.

- Desert routes filled the gaps the river couldn’t reach. Wadi routes cut through the Eastern Desert to the Red Sea, linking the Nile Valley to maritime trade with Punt and southern regions. These routes were dangerous—heat, thirst, isolation—so Egypt fortified them with wells, guard posts, and waystations. Trade here wasn’t casual; it was planned.

- To the northeast, overland routes led through Sinai into the Levant, supporting mining expeditions and caravan trade. To the south, the Nile itself extended into Nubia, forming both a trade corridor and a military frontier.

- So when asking how did ancient Egyptians trade, the answer starts with geography. The Nile didn’t just support life—it organized movement, protected supply chains, and made large-scale trade possible centuries before roads or wheels mattered. Egypt didn’t conquer distance. It floated on it.

Maritime Trade: Red Sea and Mediterranean Connections

Land routes moved goods. Rivers organized them. But maritime trade multiplied Egypt’s reach.

Once Egyptians learned to trust open water, trade stopped being regional and started becoming intercontinental.

The Mediterranean Sea was Egypt’s northern gateway. From ports in the Nile Delta, Egyptian ships sailed toward the Levant, Cyprus, and the Aegean world. These routes supplied Egypt with what the river valley lacked—especially cedarwood, silver, wine, olive oil, and fine pottery. In return, Egypt exported grain, papyrus, gold, linen, and crafted luxury goods. Mediterranean trade was steady, pragmatic, and deeply tied to diplomacy. A shipment of grain could stabilize a foreign city—or secure an alliance without a battle.

The Red Sea, by contrast, was about rarity and prestige.

Accessed through desert roads linking the Nile to Red Sea ports, this maritime route connected Egypt to Punt and southern trade networks. Ships sailing these waters returned with incense, myrrh, ebony, ivory, gold, exotic animals, and aromatics—materials essential for temples and royal display. These voyages were fewer, riskier, and carefully recorded. When they succeeded, they were carved into temple walls. That alone tells you their importance.

Red Sea trade also shows Egyptian adaptability. Ships were sometimes dismantled, transported across desert routes, and reassembled at the coast. Crews navigated unfamiliar waters using seasonal winds and coastal landmarks. This wasn’t casual seafaring. It was state-level logistics at work.

Together, these two seas expanded Egypt’s economic horizon. The Mediterranean fed Egypt’s material needs and political influence. The Red Sea fueled religion, symbolism, and global reach.

So when asking what did ancient Egyptians trade, maritime connections complete the picture. Ships didn’t just carry goods. They carried Egypt beyond the limits of the Nile—into wider systems of exchange that kept the civilization wealthy, respected, and connected.

Barter System and Early Forms of Currency

- Before coins clinked in pockets, value in Ancient Egypt was quieter—and more disciplined. Trade worked without money, yet rarely without structure.

- At the everyday level, exchange relied on barter. Goods moved hand to hand: grain for tools, linen for labor, fish for pottery. Simple. Direct. But here’s the part many miss—this system didn’t run on improvisation. It ran on shared agreement about value.

- That agreement was expressed through the deben.

- The deben wasn’t a coin you could carry. It was a unit of weight, usually based on copper or silver, used to measure value rather than represent it physically. A sack of grain might be priced at a certain number of debens. So might a chair, a jar of oil, or a day’s labor. No money changed hands—only goods equal to the agreed weight value.

- This mattered because it allowed complexity.

- State workers, priests, and craftsmen were often paid in rations: bread, beer, grain, oil. These payments were carefully calculated using deben-equivalent values. Taxes worked the same way. Households delivered goods, not cash, and scribes recorded everything with unsettling precision.

- For long-distance and international trade, the system became even more formal. Large exchanges were organized by the state, valued through weight standards, and settled through bulk goods and precious metals, especially gold. Silver, when available, functioned as a high-value benchmark, even if it rarely circulated as coinage.

- So while Egypt lacked currency in the modern sense, it didn’t lack an economy. What it had was standardization without monetization—a system built on trust, measurement, and record-keeping rather than metal disks.

- In other words, when asking how did ancient Egyptians trade, the answer isn’t “they bartered randomly.” They measured value, enforced consistency, and turned goods themselves into instruments of exchange. Order came first. Money came much later.

The Role of Temples and Officials in Trade

- In Ancient Egypt, trade was never just merchants meeting at markets. It was administration before negotiation. And at the center of that system stood two forces: temples and state officials.

- Temples were economic engines. Not symbols. Engines.

- They owned vast tracts of land, employed thousands of workers, and controlled enormous stores of grain, linen, livestock, and crafted goods. These resources didn’t sit idle. Temples redistributed food as wages, supplied expeditions, and exchanged surplus goods through official trade networks. When incense arrived from Punt or silver from abroad, temples were often the final destination—not as storage, but as ritual necessity.

- Religion and trade overlapped by design. Daily rituals required imported materials: incense, resins, precious metals, exotic woods. Without trade, temples could not function properly. And in Egyptian belief, if the gods weren’t sustained, order itself began to crack. Trade, in this sense, upheld cosmic balance—not just the economy.

- Officials made it all move.

- High-ranking administrators planned expeditions, negotiated exchanges, and supervised transport. Scribes tracked every sack of grain, every deben of value, every delivery. Nothing moved unrecorded. Trade missions to Sinai, Nubia, or Punt were led by royal agents, guarded by soldiers, and supplied through state channels. Private trade existed, but large-scale exchange belonged to the bureaucracy.

- This system gave Egypt an advantage. Central control reduced risk. Standardized valuation reduced conflict. And because officials acted in the name of the pharaoh, trade doubled as diplomacy. Foreign goods entering Egypt were proof that order extended beyond its borders.

- So when asking how did ancient Egyptians trade, the answer isn’t “freely.” It was managed, recorded, and enforced. Temples concentrated wealth. Officials directed its movement. Together, they turned trade into a tool of stability, power, and belief.

How Trade Influenced Egyptian Art and Culture?

Art never grows in isolation. Egyptian art may look timeless and self-contained, but trade quietly widened its vocabulary.

Start with materials. Many of the most striking elements in Egyptian art came from beyond the Nile Valley. Lapis lazuli, with its deep blue glow, entered Egypt through long trade chains stretching toward Central Asia. It became the color of gods, heavens, and royal power. Silver, rarer than gold in Egypt, reshaped elite jewelry and ritual objects. Ivory and ebony allowed sculptors to work with contrast, texture, and luxury previously unavailable.

Then came motifs and forms

- Trade introduced new shapes, patterns, and ideas—filtered, not copied. Foreign pottery influenced vessel design. Imported animals appeared in reliefs and wall paintings.

- Scenes of tribute and trade expeditions filled temple walls, not as decoration, but as narrative proof that Egypt stood at the center of a wider world. When Egyptians depicted Punt or Nubia, they weren’t just documenting geography. They were defining identity through contrast.

- Cultural influence flowed through daily life as well. Perfumes, cosmetics, and incense, all tied to foreign trade, shaped rituals, fashion, and burial practices. Smell mattered in Egyptian culture—purity, divinity, presence. Trade made those sensory experiences possible.

- Even writing and symbolism felt the impact. Papyrus exports connected Egypt intellectually to other civilizations, while imported goods reinforced hieroglyphic symbolism. Blue stones meant divinity. Exotic animals meant dominance. Foreign materials became visual shorthand for power.

- What’s important is this: Egypt absorbed without losing itself. Trade didn’t dilute Egyptian art or culture—it refined it. Foreign elements were stripped of their origins and reassembled inside Egyptian logic, order, and belief.

- So when asking how trade influenced Egyptian art and culture, the answer is subtle but decisive. Trade expanded Egypt’s material palette, enriched its symbolism, and allowed its culture to speak not just to itself—but to the world watching from beyond its borders.

Ancient Egyptian economy

- Every civilization runs on a quiet agreement with reality. Egypt’s agreement was simple: the Nile provides, the state organizes, and society endures.

- The Ancient Egyptian economy was not driven by markets in the modern sense. It was driven by agriculture, redistribution, and control. At its core stood the Nile’s annual flood, which renewed the soil and made large-scale farming predictable. That predictability changed everything. When harvests can be anticipated, surplus can be planned. When surplus exists, power can be centralized.

- Agriculture formed the foundation. Most Egyptians were farmers, and most economic value began as grain. Wheat and barley fed the population, paid workers, stocked granaries, and fueled trade. Grain was wealth—not symbolically, but literally. It functioned as food, tax, wage, and export.

- Above the fields stood the state.

- Land was technically owned by the pharaoh, administered through officials, and worked by the population. Taxes were collected in goods, recorded by scribes, and redistributed to temples, workers, soldiers, and artisans. This redistributive economy meant wealth flowed upward, then back downward in controlled channels. Stability mattered more than profit.

- Craft production added another layer. State-run workshops produced linen, tools, pottery, jewelry, and luxury items. Skilled labor wasn’t freelance; it was organized, supplied, and fed by the system. Payment came in rations, not wages. Bread and beer sustained the workforce that built temples and tombs.

- Trade connected the economy outward. Exports like grain, gold, papyrus, and crafted goods balanced imports of wood, metals, and incense. Large-scale trade was managed by officials, not merchants chasing margins. The goal wasn’t growth—it was balance and security.

- What makes the Ancient Egyptian economy distinctive is this: it prioritized order over expansion. No obsession with accumulation. No uncontrolled markets. Just enough surplus, carefully managed, to keep society functioning, gods honored, and borders supplied.

- So when we talk about the Ancient Egyptian economy, we’re really talking about a system designed to resist chaos. Predictable land. Predictable administration. Predictable flow of goods. In a world of uncertainty, Egypt built an economy that made permanence possible.

Suggested:

How did taxation benefit ancient egypt?

- Taxes rarely sound noble. In Ancient Egypt, they were foundational.

- Taxation worked because it aligned perfectly with Egypt’s economic reality. There was no widespread money, so taxes were paid in goods and labor—mostly grain, livestock, textiles, and time. This system turned individual production into collective stability.

- First, taxation secured food supply. Grain taxes filled state granaries, which acted as Egypt’s insurance policy. In years of low floods or poor harvests, stored grain prevented famine. That alone explains why taxation benefited Ancient Egypt more than it burdened it. Survival depended on foresight, not charity.

- Second, taxes funded the state apparatus. Officials, soldiers, scribes, and craftsmen were all supported through redistributed tax goods. Roads, irrigation canals, storage facilities, and transport fleets didn’t appear on their own. Taxes paid for the infrastructure that kept agriculture productive and trade moving.

- Third, taxation enabled monumental construction. Temples, tombs, and pyramids weren’t built with money; they were built with taxed labor and resources. During flood seasons, when farming paused, workers were reassigned to state projects. Taxation transformed idle months into national achievement.

- There’s also a political layer. Tax collection reinforced central authority. By measuring land, recording yields, and collecting dues, the state made its presence unavoidable. This wasn’t oppression—it was administration. Predictable taxes meant predictable obligations, which reduced conflict and uncertainty.

- Finally, taxation supported religious continuity. Temples received tax allocations to maintain rituals, festivals, and offerings. In Egyptian belief, these rituals sustained cosmic order. Taxes, indirectly, kept the universe in balance.

- So when asking how did taxation benefit Ancient Egypt, the answer is structural. It fed the population, funded governance, built monuments, stabilized society, and reinforced belief. Taxes weren’t just taken. They were transformed—into food security, order, and permanence.

FAQ

What did ancient Egyptians trade the most?

Grain was the backbone. Thanks to the Nile, Egypt consistently produced surplus wheat and barley, which became its most important trade good. Alongside grain, Egypt traded linen, gold, papyrus, and crafted luxury items.

Did ancient Egyptians use money for trade?

Not in the modern sense. Early Egyptian trade relied on barter, with value measured using the deben, a unit of weight. Goods and labor were exchanged based on agreed standards rather than coins.

Who controlled trade in Ancient Egypt?

Large-scale trade was mostly state-controlled. Officials organized expeditions, temples managed surplus goods, and scribes recorded transactions. Private trade existed, but international and strategic trade remained under royal supervision.

Why was trade so important to Ancient Egypt?

Because Egypt lacked key resources such as timber, silver, and large amounts of copper. Trade allowed Egypt to obtain these essentials while exporting what it had in abundance. Trade supported the economy, religion, political power, and long-term stability.

Who were Egypt’s main trading partners?

Egypt traded with Nubia, the Levant, Sinai, the Aegean world, and the land of Punt. Each partner supplied specific materials—gold, wood, metals, incense—that Egypt could not easily source locally.

How were goods transported within Egypt?

Primarily by the Nile River, which acted as a natural highway. Boats carried heavy goods efficiently, while desert routes and maritime paths connected Egypt to the Red Sea and Mediterranean trade networks.

Did trade influence Egyptian culture and art?

Yes, deeply. Imported materials like lapis lazuli, silver, and incense shaped art, jewelry, religious rituals, and symbolism. Trade expanded Egypt’s cultural expression without weakening its identity.

Was Ancient Egypt a market economy?

No. It functioned as a redistributive economy. Goods flowed from producers to the state through taxes, then back to society through wages, rations, and temple support. Order and stability mattered more than profit.

Conclusion

Trade was never a side activity in Ancient Egypt. It was part of the civilization’s architecture.

From the first exchange between neighboring villages to voyages across the Red Sea and Mediterranean, trade answered Egypt’s deepest limitations and amplified its greatest strengths. The Nile created surplus. The state organized it. Trade extended its value far beyond Egypt’s borders.

When we ask what did ancient Egyptians trade, we uncover more than lists of goods. We see grain used as power, gold as diplomacy, incense as belief, and craftsmanship as identity. Imports filled material gaps. Exports projected stability. Routes became arteries. Temples became warehouses. Officials became economists before the word existed.

What’s striking is not how much Egypt traded, but how deliberately it did so. Exchange was measured, recorded, and controlled. The goal wasn’t endless growth. It was balance—between scarcity and surplus, isolation and influence, earth and belief.

That balance is why Egypt endured.

Trade didn’t just move goods. It sustained order, reinforced culture, and allowed a river-bound society to think globally thousands of years before globalization had a name.

Leave a Reply