hatshepsut facts

To be Pharaoh was the greatest, the most sacred game under the Egyptian sun. Pharaoh was the son of the sun. He spoke to the gods, he let the rain fall and the Nile burst its banks fruitfully. Because it stood for “maat”, the divine truth, the order of all things. As a man. With a beard and testicles. The rule always passed from father to son or a close confidante – or even competitor. In any case, however, from man to man – and definitely when the old Pharaoh died and began his journey to the hereafter to connect with Osiris, the ruler of the realm of the dead.

Rule in ancient Egypt was a man’s business

This is what happened in 1479 BC. When Pharaoh Thutmose II died: his son Thutmose III. followed him. But then someone else seized power. Pharaoh Maatkare. At least that was his throne name: “Justice and vitality, a re”. The tomb of Pharaoh Maatkare in the Valley of the Kings is half-buried, his mummy missing, and the hieroglyphs of his name have been carved from obelisks, scratched from temple walls and scraped from pillars. It disappeared from history for more than 3000 years. Because Maatkare, the incarnate man, was a woman.

“The first of the ladies” was her name: Hatshepsut. A female pharaoh who simply took power over the two countries, Upper and Lower Egypt, was unprecedented in the state. An unbelievable process. Hatshepsut was the most powerful woman who ever lived on the Nile. After the death of her husband Thutmose II, she was at the head of Egypt for two decades, replacing the still underage Thutmose III.

Hatshepsut, the most powerful woman on the Nile

Women who temporarily ruled as regents for childish heirs to the throne had existed on the Nile even before Hatshepsut. But sometime between the 2nd and 7th year of her reign, Hatshepsut took on something monstrous: She made herself Pharaoh; the queen became a king – Pharaoh Maatkare. It is true that she always had the heir to the throne officially listed as co-ruler. From now on, however, Egypt’s politics were determined solely by them.

Three archaeological teams are currently researching and working on the monuments, which tell of Hatshepsut and its age with their speaking stones. Polish scientists are reconstructing their mortuary temple in Deir el-Bahari. The French have rebuilt the Red Chapel. And Americans interpret the reliefs in the Little Temple of Medinet Habu. All of them – Egyptologists, archaeologists, art historians, restorers, architects, stonemasons – try to talk to Hatshepsut. That woman who symbolically changed her sex for power in the land and became Pharaoh.

Stones tell of the female pharaoh

The rise of the Theban kings to the top of Upper and Lower Egypt begins about 50 years before Hatshepsut’s birth, around 1550 BC. At that time, at the beginning of the New Kingdom, Thebes experienced a great boom. Because it is Theban princes who succeed in driving those foreign rulers from the area of Palestine who have been ruling northern Egypt for about 100 years. First and foremost, Ahmose storms, whom the lists of kings will later list as the first pharaoh of the 18th dynasty.

Ahmose I ruled for 25 years and left his son Amenophis I a united Egypt with secure borders. Since Amenhotep did not have a surviving son, someone else was appointed Pharaoh: Thutmose I, who lived in 1504 BC. BC ascends the throne. He is Hatshepsut’s father – and that of her husband and half-brother Thutmose II. With the kings of the 18th dynasty, Thebes rose to become the capital of Egypt. And Amun, the local god of Thebes, to the greatest of the more than 500 gods on the Nile. Amun’s place of worship on the east bank of the river is growing into the mightiest temple city in the country.

Divine generation as justification

Now these buildings are no longer just temples of the cult of the dead, but places of mutual veneration of Amun and Pharaoh. Hatshepsut goes the furthest: Since she later has to permanently justify herself to the priests and the civil servants for her seizure of power, she declares Amun to be her biological father and has the images of her divine procreation carved into the walls of the temple dedicated to her as further legitimation. Her life becomes: a myth.

But why did Hatshepsut decide to become pharaoh at all, to replace her previous life story with a myth and to give up her identity as a woman? And why did the priests, why did Egypt accept the coronation of a woman without a riot?

Careful assumption of power

During her marriage to Thutmose II, Hatshepsut was apparently an exemplary wife and mother. Inconspicuous and always in the background on displays. There is no evidence to suggest that she was ever dissatisfied with her role. With the death of her husband and the beginning of her provisional rule, however, she must have found pleasure in power. This is the only way to understand that she has so openly challenged the divine order and the priests.

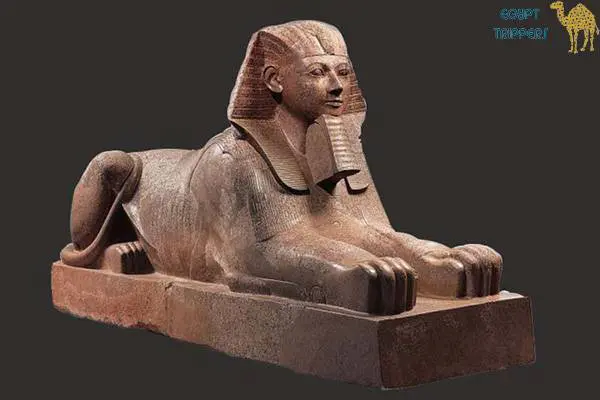

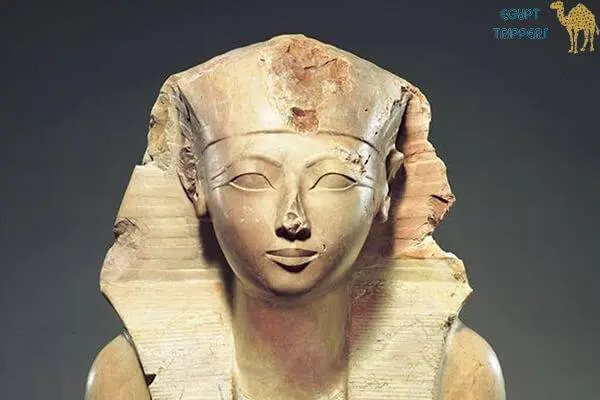

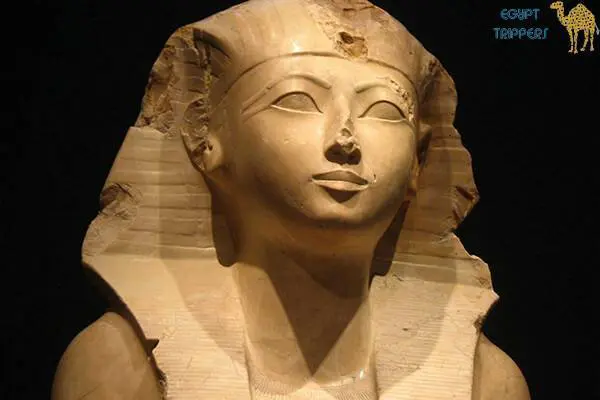

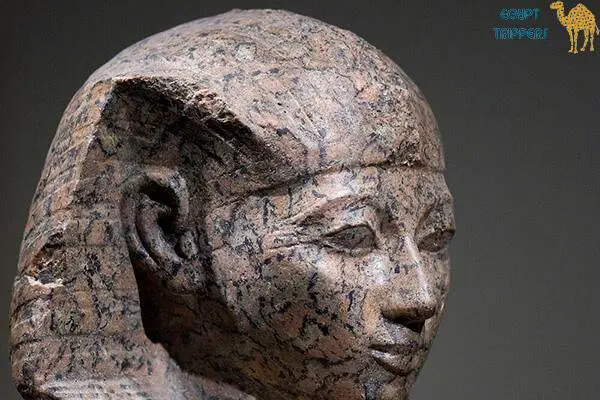

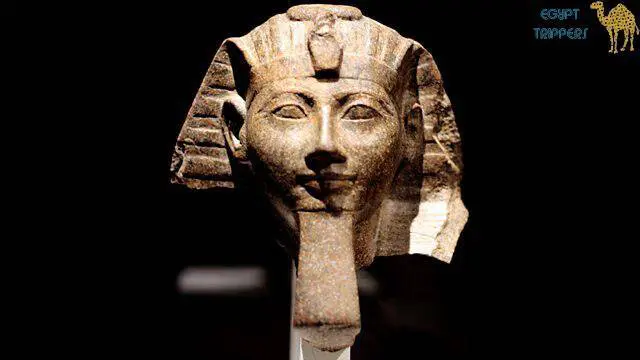

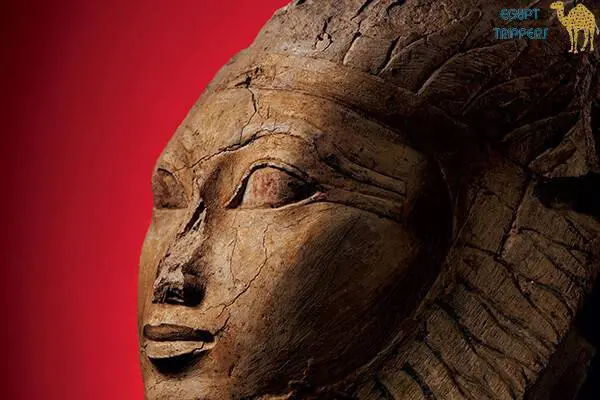

However, she did not seize power in an act of violence, but carefully prepared her coronation. The daughter of Thutmose I knew about her opponents and gathered powerful supporters around her, including among the clergy. And even after her coronation she proceeded cautiously, constantly striving for legitimation. The statues and portraits of Hatshepsut that still exist today show her path in a unique way.

The woman at the top gradually became a man

First of all, the ruler can be portrayed as a female pharaoh, wearing a king’s headscarf, but with breasts and a dress. Then, little by little, their official picture changes. She takes off her clothes. From then on dressed in the short pleated apron of kings. Your breasts shrink, your features become harder, your shoulders broader. After all, she even wears the pharaohs fake beard. The woman at the top of Egypt has finally become a man.

But the revolutionary on the pharaoh’s throne may want to go one step further: namely, make her daughter Neferure her successor. And with it the rightful heir to the throne Thutmose III. pass over for good. As a toddler, Hatshepsut declared Neferure to be the “wife of God of Amun”. Until then, this priesthood was exercised in the New Kingdom only by those women who were destined to become the wife of a pharaoh.

Daughter as successor on the throne?

Since Neferure but apparently never with Thutmose III. has been married, it could be – at least as some Egyptologists suspect – that Hatshepsut intended from the beginning to establish her daughter as her successor thanks to this title. However, the scientists will probably never be able to conclusively clarify whether this thesis is to be taken seriously. Because around 1470 BC Neferure suddenly disappears from the testimonies of that time. Hatshepsut’s possible successor probably died at a young age.

The southern portico of the central terrace at the mortuary temple is filled with depictions of Hatshepsut’s greatest success: the expedition to Punt. It is the protocol of a trade mission that Hatshepsut 1470 BC. Can equip. Five ships are sent to the Horn of Africa with the task of exchanging luxury goods, especially incense for the rituals in the temple. The mission lasts three years. The scenes and images show a self-confident ruler who already seems to be at the zenith of her power and rules a wealthy empire.

Hatshepsut: the confident ruler

The legendary land of Punt was probably in what is now Somalia or Eritrea. In Punt, Egypt exchanged gold, frankincense, myrrh, hides, precious stones, ivory and ebony. The pictures of Deir el-Bahari are probably the oldest and most detailed depictions of East Africa. They show dwellings, cattle, giraffes, leopards and animals whose outlines are reminiscent of rhinos. The huts of the people of Punt resemble beehives on stilts, apparently woven from palm fronds. Parehu, the prince of Punt, can also be seen: a slender man, accompanied by his shapeless, fat wife.

A lot of space is given to the depictions of the ships in the portico: one-masters made of wood that are not only sailed but also rowed. You can see how sailors gesticulate wildly, monkeys play in the rigging, how buckets with myrrh trees are carried over swaying planks on board on carrying bars. Heavily laden with sacks, bales, jugs and chests, the ships leave with billowing sails.

The boom of trade

Back on the Nile, the treasures of the frankincense land are spread out. If the man-high piles of incense are measured with bushels and the chests with gold, the precious metal rings, panthers, ostrich eggs and feathers, elephant tusks, ebony, and even a giraffe are presented. And you can see that Pharaoh Maatkare dedicates these treasures to Amun, the god of the state. As a gift and as a sacrifice. The message from these scenes is unmistakable: trade is flourishing under Maatkare. The country is rich. The blessings of the gods rests on Egypt.

That’s pretty close to the truth. Hatshepsut’s reign was stable and largely peaceful. The borders of the empire, which ran across the Sinai Peninsula to the north and deep into Nubia to the south, were secure. Magnificent new buildings have been erected all over Egypt, and the country, which has a population of perhaps three million people, appears to have enjoyed rich harvests. There is nothing in these pictures to suggest that anyone tried to rebel against the Pharaoh, who was born a woman.

Stonemasons erased names and portraits of the regent

Around 1458 BC BC, the 22nd year of his reign, Pharaoh Maatkare simply disappears. Thutmose III. finally becomes the sole king of Egypt after two decades of waiting. And then, sometime in the later years of his reign (which lasted until 1425 BC), an iconoclasm sets in that obliterates the memory of Maatkare / Hatshepsut for more than 3000 years.

The stonemasons rage for weeks with bronze chisels to destroy as many cartouches, hieroglyphs, statues and pictures as possible that show Hatshepsut. In the mortuary temple of Deir el-Bahari, every representation of her name is pried away, other names are carved into the spaces. Little escapes the destruction, including some statues – and the hidden cartouches on top of the pillars of the mortuary temple.

The memory of the ruler lasted over time

Why was Hatshepsut so ostracized? Was suddenly the existence of a female pharaoh, even if he was long dead, an open declaration of war on Maat, the divine order? Or did Thutmose III want. simply forget that he, the great warlord who commanded 17 campaigns to Asia during his tenure, had been passed over by a woman for so long?

Only this much is clear to Egyptologists: representations and hieroglyphics had a magical power in ancient Egypt. And people believed they could undo an event by erasing every image and sign that told of it, but they were unable to erase the memory of that woman who turned into a man more than 3,000 years ago To become pharaoh.

Leave a Reply